The Tragedy of Forest Buerer

/The Henry and Margaretha Buerer family. Forest standing between his mother and father.

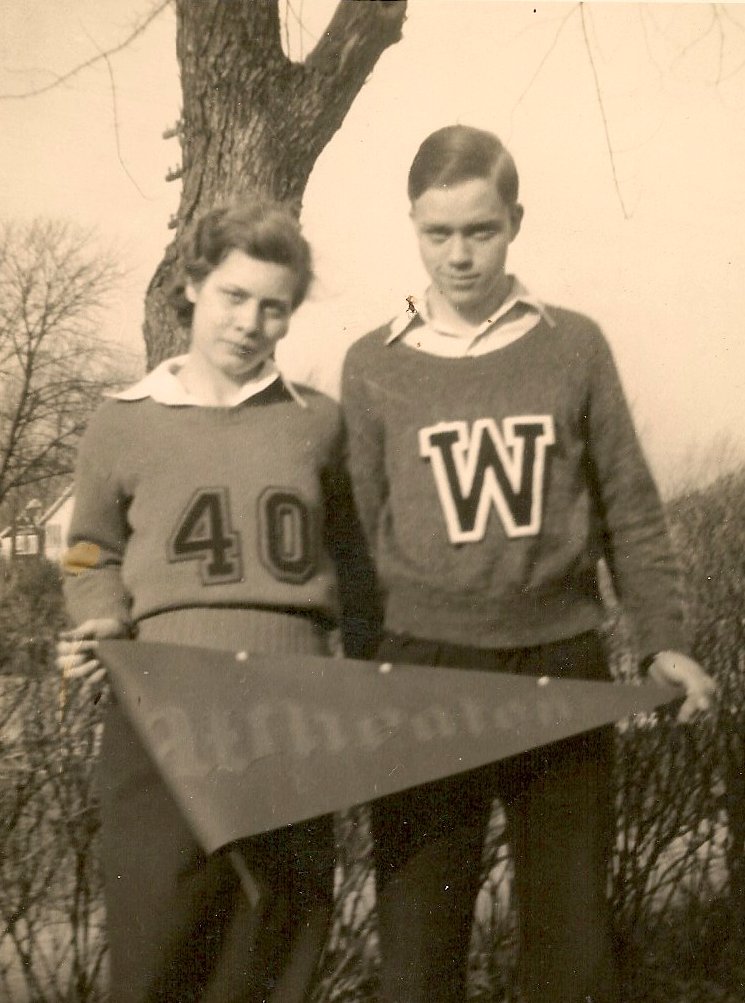

By the time my two-times great grandmother, Margaretha Schwab Buerer, turned 45 years of age in 1898, she had traveled more miles than most people did in a lifetime. Born to German immigrants, Johann Heinrich Schwab and Anna Margareta Kuhl, in Lee County, Illinois, in 1853, Margaretha married Henry Buerer in 1873, and settled into a life of farming in Clay County, Nebraska until 1894, when Henry was encouraged to go west to relieve his back pain and severe headaches. Unfortunately, in 1897, Henry succumbed quickly to a severe case of pneumonia, and left Margaretha a widow and single mother of eight living children (giving birth to 11 total.)

After a trip back to Nebraska to sell the family farm, Margaretha then returned with her children to the West Coast, starting a saw mill in Marion, Oregon. Obviously a strong woman from what she had endured, she couldn’t save her seventh born child, Forest, from a terrible accident.

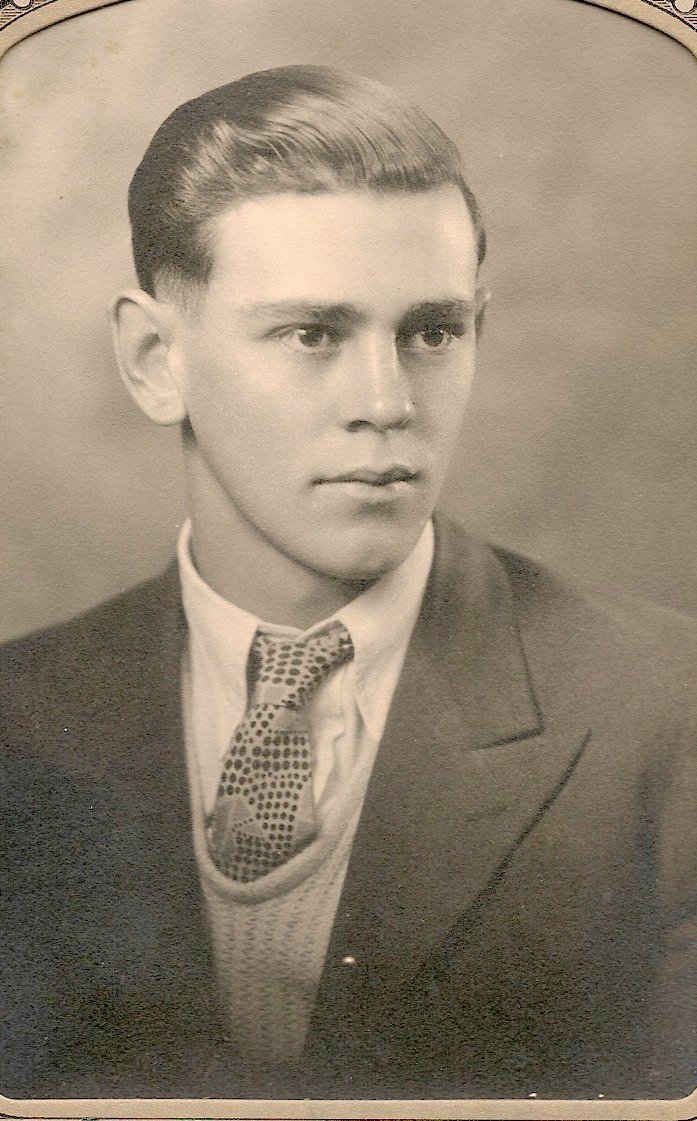

On the evening of June 16, 1905, Forest and his brothers became caught up in the transportation of timber, where Forrest met an untimely end.

Drowned at the Veal Mill*

Forest Buerer was drowned last Saturday evening in the pond of the saw mill of Veal & Sons, on the Santiam this side of Marion. It was an unfortunate accident. Forest Buerer and his brothers had the contract for running logs down the Santiam to the mill of Veal & Sons. In the spirit of fun he started to roll a log across the pond. His mother was on the bank watching him. Out in the deep water the log began rolling, he was thrown in, strangled, and though a good swimmer, was drowned, with his mother watching him. A brother was coming but was too far away to render assistance. He was 20 years of age.

The funeral will be held tomorrow at 2 o’clock, being delayed to give a brother in Nebraska time to attend.

Forest Phillip Buerer is buried in the Marion Friends Cemetery in Marion, Oregon.

Margaretha Schwab Buerer died in 1932 at the age of 79 in San Jose, California.

*“Drowned at the Veal Mill.” The Albany Democrat (Albany, Oregon), 23 June 1905, p. 3, col. 2; digital images, Newspapers.com (https://www.newspapers.com/image/96018481: accessed 24 April 2016).